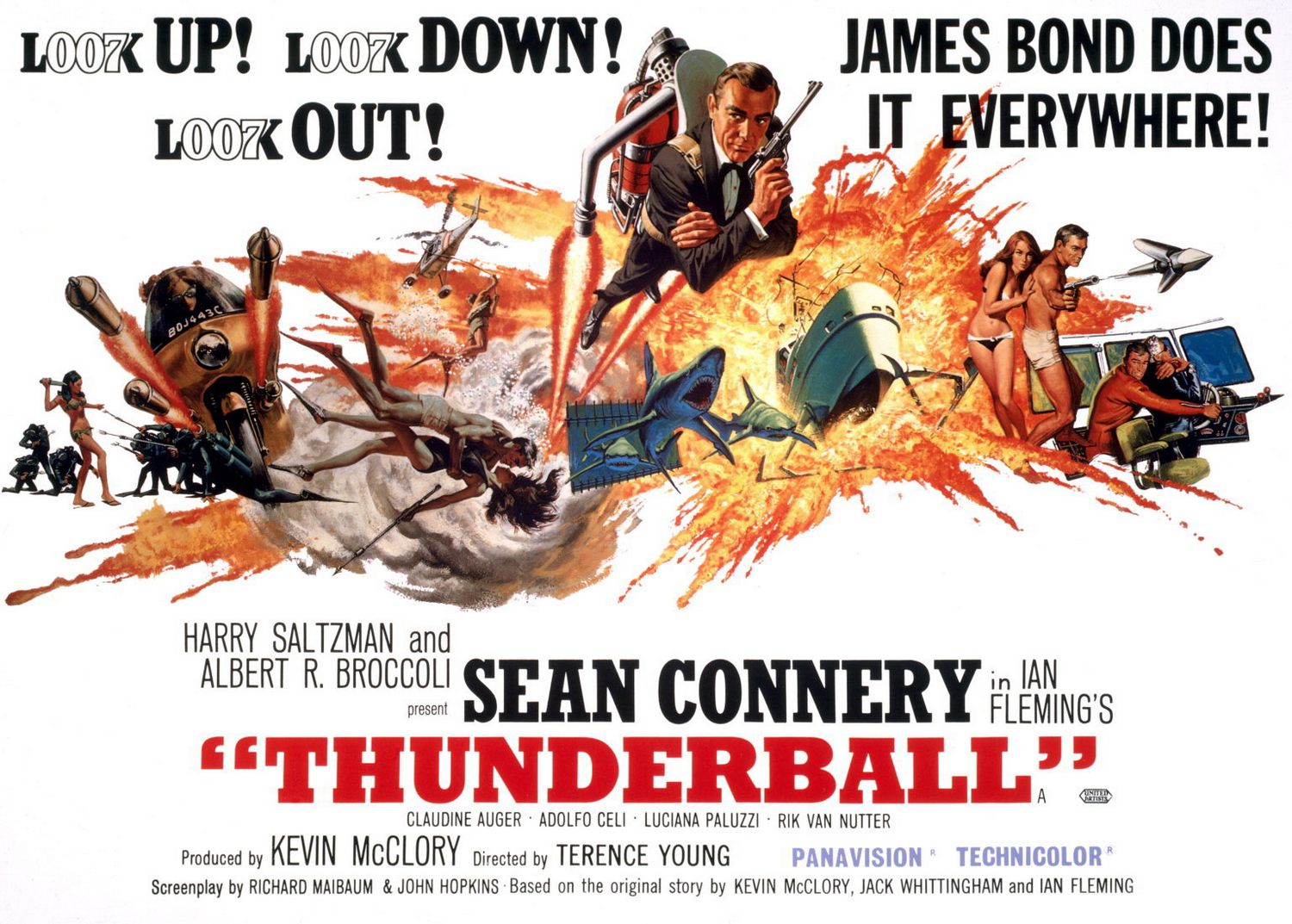

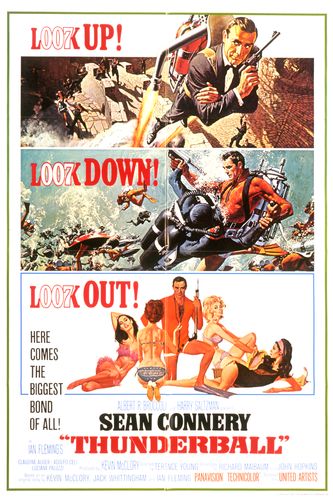

| Det har varit mycket bråk om rättigheterna till "Åskbollen" under

åren. På denna sida skall jag försöka bena ut hela historien. Man skall

dock tänka på att vissa detaljer av historien varierar beroende på vem

man talar med och därför kan det hända att något på denna sida kan vara

avvikande från vad som egentligen hände. Men, så vitt jag vet, så var

det så här: Först en mycket nedkortad version

av händelserna, för de av er som inte orkar läsa allt:

Ian

Fleming skrev 'Thunderball' som ett manus tillsammans

med ett par andra. Sedan gav han ut manuset i bokform och blev han stämd

och domstolen beslutade att Fleming skulle få bokrättigheterna och Kevin

McClory, den av medförfattarna som stämde Fleming, fick

filmrättigheterna.

Nu till den mer utförliga historien:

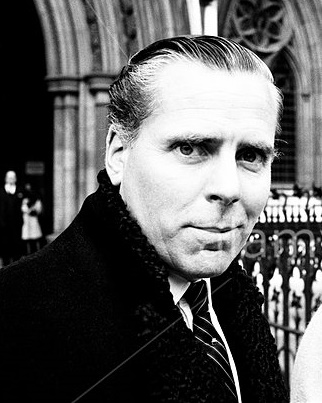

1958 introducerade Ian Flemings vän, Ivar

Bryce, honom för den unge (33 år) regissören Kevin McClory.

Bryce hade inlett ett samarbete med honom och bildat bolaget 'Xanadu

Productions' (efter namnet på Bryce hus på Bahamas) för att filma

McClorys film, 'The Boy And The Bridge'. McClory upptäckte

Flemings böcker och förstod att de kunde göra sig mycket bra på den

biograferna. Ian Fleming hade vid denna tid börjat bli lite desperat, då

inget filmbolag verkade vara intresserad av att filma hans böcker, så

han blev glad över McClorys entusiasm.

1959 hade Fleming, McClory ett mer eller mindre

muntligt avtal om att Fleming skulle skriva en ny historia till filmen,

då de inte ville ta någon som redan fanns i bokform. Bryce skulle

producera och McClory skulle regissera och dessutom hjälpa Fleming med

att skriva manuset.

Ernest Cuneo, Flemings och Bryces amerikanske vän från andra

världskriget, blev också involverad efter ett tag.

Under en lång helg i maj 1959, blev Bryces hem Moyns

Park i Essex, arenan för en stor brainstorm för de fyra männen. Det var

där som de kom fram till många idéer om filmen. McClory ville ha många

undervattensscener, då han var intresserad av dykning. Cuneo kläckte då

idén om att förlägga storyn på Bahamas. Detta var att föredra av flera

skäl. Det var ett billigt ställe att spela in på, det skulle underlätta

kontakter med Hollywood samt att det skulle bli billigare av

skattetekniska skäl. Bryce och McClory hade dessutom hus på Bahamas.

McClory skrev ner alla idéer som kommit fram under helgen. Namnförslag

på filmen var så här länge antingen 'James Bond Of The Secret

Service' eller 'James Bond, Secret Agent' och

storyn handlande om ett gäng skurkar utpressade ett flertal länder och

hotade med att detonera ett par stulna atomvapen.

Under denna tid var det maffian som låg bakom dådet. SPECTRE uppfanns

inte förrän senare då Fleming använde manuset till sin bok,

""Åskbollen".

Tilläggas bör att det kan ha varit så att det var Cuneo som kom

på den grundläggande historien till manuset från början.

De fyra var under den här tiden även exalterad över det faktum att

McClory och Bryces film, 'The Boy And The Bridge', hade blivit

utsedd till Storbritanniens officiella bidrag till filmfestivalen i

Venedig.

Efter den helgen skildes de fyra åt, med löften att hålla de övriga

underrättade med hur manuset framskred, men i juli 1959

hade 'The Boy And The Bridge' premiär i England och den gick

uruselt, vilket gjorde att Fleming och Bryce blev oroliga för

Bondprojektet. Relationerna mellan Fleming/Bryce och McClory blev av

detta ganska svala. Kanske trodde de att McClory var för ung och

oerfaren för ett projekt i denna storlek. En annan faktor var att MCA,

Flemings agentur, hade fått känning från flera stora filmbolag som

verkade vara intresserade av James Bond.

Ju längre projektet gick, växte det i storlek och kostnad. Bryce hade

förlorat mycket pengar på 'The Boy And The Bridge' och MCA sade

till Fleming att en mer erfaren regissör skulle locka till sig mer

pengar från Hollywood. Det var antagligen vid denna tid som Fleming och

Bryce tappade förtroendet för McClory, som fortfarande satt och jobbade

med manuset, som nu hade fått namnet 'Longitude 78 West'

I september 1959 hölls ytterligare ett möte där

Fleming föreslog att ta in en annan regissör, och att McClory skulle

producera. Motvilligt gick McClory med på förslaget, då han trots allt

var kvar som producent och manusförfattare. Bryce hade tagit en mer

tillbakadragen roll, som i dag skulle kunna kallas "Executive Producer".

Vid oktober samma år hade Fleming börja att ägna

mindre tid åt projektet, då han blivit engagerad av Sunday Times att

skriva en artikelserie kallad ´Thrilling Cities', vilket tvingade honom

att göra en fem veckor lång jorden runt-resa.

McClory anställde då en ny författare, Jack Whittingham, för att

hjälpa honom att slutföra manuskriptet. Något som både Fleming och Bryce

gick med på.

I december skickade McClory och Whittingham den

senaste versionen av manuset till Fleming, som tyckte om det, men var

fortfarande lite reserverad angående filmens budget. Titeln hade han

dock inte så mycket över för och ändrade den till 'Thunderball',

samt skrev till i manuset att Bonds uppdrag gick under namnet "Operation

Thunderball".

Under den kommande månaderna tappade Fleming mer och mer förtroendet

till McClory och Fleming (tillsammans med Bryce) började fundera på

McClorys position i den kommande filmen.

I januari 1960 kom McClory till Flemings hem,

Goldeneye, för att diskutera det senaste utkastet av manuset. Fleming

berättade då att han och Bryce var beredda att lämna över hela projektet

till MCA med rekommendationer att McClory skulle vara producent. Men om

MCA eller någon filmstudio skulle avslå projektet på grund av McClory

skulle vara producent, skulle McClory backa och låta projektet fortsätta

med en ny producent.

Filmprojektet hade helt enkelt blivit för stort för Fleming och Bryce

att klara av ensamma.

Cuneo hade helt lämnat alla intressen för projektet, då han tyckte att

bara hade hjälpt sina vänner lite i idéstadiet. Han sålde alla

eventuella rättigheter i projektet till Bryce för den symboliska summan

av en dollar.

Då det såg ut som att projektet skulle rinna ut i sanden, samt att

Fleming hade press från sitt bokförlag att skriva en ny Bondbok, tog han

den grundläggande storyn i 'Thunderball' och skrev om den till en roman.

Om han medvetet menade att stjäla manuset från McClory och Whittingham,

kan diskuteras. Fleming var, å ena sidan naiv när det gällde show

business, men å andra sidan så kan han och Bryce tänkt att medvetet köra

över den yngre (och irländske) McClory. Fleming dedicerade boken till

Cuneo, som en litet erkännande till historiens ursprung.

1961 publicerades boken "Thunderball'

och McClory blev givetvis chockad och arg över att Fleming använt storyn

utan varken hans eller Whittinghams godkännande och stämde Fleming.

En snabb rättslig process gav bokförlaget rättigheterna att kunna

fortsätta publicera boken, då så många exemplar redan skickats till

butikerna. En slutlig prövning av fallet skulle komma senare, men det

skulle ta ytterligare två år.

Och under de två åren skulle det hända mycket med James Bond.

I slutet på 1960 köpte

Harry Saltzman en option på en kommande James Bond-bok och

1961 bildade han och

Albert R. Broccoli bolagen Danjaq S.A. och EON Productions

Limited. United Artists gick med på att hjälpa till med den första

filmen.

"Thunderball"

hade precis kommit ut och blivit en stor succé, vilket gjorde att

Broccoli och Saltzman valde denna till sin första film. Broccolis vän

Richard Maibaum anställdes för att skriva om boken till ett

filmmanus (trots att det redan existerade ett färdigt manus plus ett

flertal utkast!). Men då det kom fram att rättigheterna till detta manus

var under utredning fick de lägga "Thunderball" åt sidan och de valde

boken "Dr.

No" istället.

Sean Connery spelade Bond och

filmen hade premiär i England i oktober och resten är historia...

Men i november 1963, strax efter att den andra

filmen, 'From

Russia With Love' haft premiär, började den slutliga prövningen

av fallet.

Broccoli och Saltzman hade börjat med förberedelserna till den tredje

filmen, 'Goldfinger'

och var självklart nervösa över vad domen kunde medföra. Fleming senaste

bok, "On

Her Majesty's Secret Service", var hans största succé hittills

och hans nästa bok, "You

Only Live Twice", skulle publiceras under våren 1964. James Bond

hade vuxit enormt sen sist och mycket stod på spel.

I rättssalen var det McClory mot Fleming (för plagiat) och Bryce (för

kontraktsbrott [Xanadu Productions]). Det var meningen att Jack

Whittingham skulle varit vid McClorys sida i stämningen mot Fleming, men

han hade inte råd i detta läge och var endast med som vittne.

Whittingham stämde dock Fleming senare, men åtalet lades ner efter

Flemings död 1964.

Fleming hade redan fått sin första allvarliga hjärtattack och var svårt

sjuk under de tre veckor som rättegången pågick.

McClory hade starka bevis på att han hade rätt, medan Fleming ansåg att

originalidén kom från Cuneo, som hade sålt sina rättigheter till Bryce.

Det var till slut Bryce som, på grund av McClorys starka bevis och

Flemings vacklande hälsa, som gick med på en kompromiss.

Uppgörelsen gick ut på att Fleming fick bokrättigheterna, så länge alla

kommande upplagor av boken skulle innehålla ett meddelande att den var

baserad på ett manus av Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham och Ian Fleming.

Han fick även rättigheterna till karaktären James Bond.

McClory fick film- och TV-rättigheterna (inklusive då rätten att använda

personen James Bond vid detta/dessa tillfällen), samt copyrighten på

alla existerande manus och utdrag av boken. I dessa manus fanns

dokumenterat ytterligare nio olika manusbehandlingar och utkast.

Bryce fick betala en okänd summa till McClory och Whittingham för

skadestånd, samt betala de rättsliga kostnaderna för alla inblandade.

Den slutliga summan låg på cirka 85 000 pund.

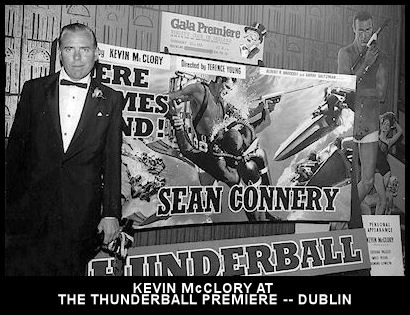

Nu när McClory äntligen hade rättigheterna att göra sin egna Bondfilm,

brydde han sig inte så mycket om att EON hade gjort en serie Bondfilmer

som blivit populära, utan började leta efter skådespelare som kunde

spela Bond.

Broccoli och Saltzman ansåg givetvis att denna konkurrerande Bondfilm,

skulle skada deras egna filmer och beslöt sig för att fråga McClory om

han var intresserad av ett samarbete. McClory skulle få stå som ensam

producent, trots att de alla tre producerade filmen. McClory godtog

detta och i avtalet gick McClory också med på att inte använda sina

"Thunderball"-rättigheter under de tio kommande åren efter att filmen

släppts och att Danjaq S.A. skulle ha de fortsatta rättigheterna för den

filmen som de gjorde 1965.

Ett nytt, uppdaterat, manus skrev till filmen av

Richard Maibaum och John Hopkins.

Efter att tio årsperioden tog slut försökte McClory göra en ny Bondfilm

med det material som han hade rättigheterna till.

Den 12 maj 1976 lade han ut en helsidesannons i

tidningen Variety som sade att filmen 'James Bond Of The

Secret Service' skulle börja filmas i februari

1977.

Manuset skrivs tillsammans med

Sean Connery och thrillerförfattaren Len Deighton och namnet

på filmen ändrades till 'Warhead'.

United Artists och Danjaq svarade på dessa förberedelser

också genom en helsidesannons i Variety, där de sade att de hade

alla rättigheter på allt som hade med James Bond att göra förutom boken

"Åskbollen"

och att McClorys film endast var en ytterligare en filmatisering av

denna.

De två företagen flåsade McClory rejält i nacken och deras juridiska

maskineri gick hårda matcher med honom. Till slut insåg Connery vilka

problem de stod framför bara att göra filmen, så han gick därifrån.

Detta gjorde det inte lättare för McClory och projektet rann till slut

ut i sanden.

Eftersom SPECTRE och Blofeld skapades i samband med "Thunderball",

ligger frågan om vem som egentligen äger rättigheterna till dem i den

rättsliga gråzonen. EON har dock klokt nog undvikt att blanda in dem

efter filmen 'Diamonds

Are Forever' från 1971. 1981

års 'For

Your Eyes Only' räknas inte, då Blofeld inte nämns vid namn

varken i filmen eller i rollistan!

Runt 1980 upptäckte en av cheferna för filmbolaget

Lorimar, Jack Schwarzman, projektet. Han var på att lämna

Lorimar vid denna till för att öppna eget och 'Warhead'-manuskriptet

facinerade honom. Han var en duktigt jurist och trodde att McClory

verkligen kunde göra filmen trots alla juridiska problem, så filmen var

på igen...

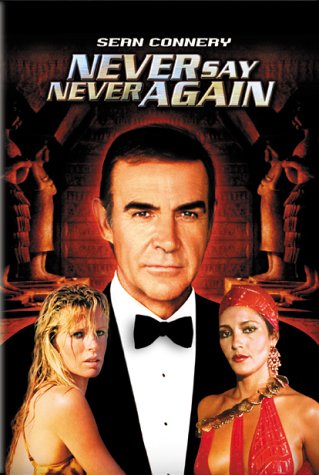

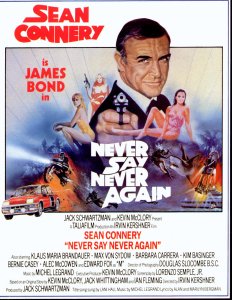

Han lyckades intressera

Sean Connery att spela huvudrollen igen. Sean tackade säkert ja av

flera skäl, hans fru tyckte han skulle göra det, det var säkert en del

pengar i potten och kanske det viktigaste skälet (?) - Connerys stjärna

var fallande och han behövde en stor film igen... Han fick dessutom

väldigt mycket att säga till om när det gällde hur filmen skulle göras

och om folket bakom och framför kameran.

Schwarzman köper även rättigheterna till denna inspelning av filmen av

McClory och han lämnar den bakom sig - för denna gång. Köpet innebar

bara att Schwarzman får göra en film av manuset och att McClory

nämns som en av producenterna i filmen ("normalt" hedersutnämning i

Hollywood). McClory har alltså inte haft någon inverkan på denna film.

Manuset skrivs om (bland annat av Schwarzmans frus bror Francis Ford

Coppola). Schwarzman slängde ut Connery/Deighton-manuset, då detta

var mer som en uppföljare till 'Åskbollen' än en remake och skulle ha

orsakat mycket juridiska problem.

Titeln ändrades till 'Never

Say Never Again' och i september 1982 så börjar

då äntligen inspelningen och efter en mycket tuff inspelning, blir

filmen klar året efter.

Den 20 juli 1989, bara några veckor efter att 'Tid

För Hämnd' haft premiär går McClory ut med hans senaste projekt,

'Warhead 8'. Ännu en nyinspelning av manuset alltså och

eventuellt skulle

Pierce Brosnan spela Bond. Inte helt förvånande rann detta projekt

ut i sanden...

1992 dök han upp igen! Denna gång skulle det göras

en TV-serie baserad på manuset. Inte heller detta blev verklighet...

Ian Fleming dog 1964, Jack Whittingham i

slutet av sjuttiotalet. Ivar Bryce avled

1985 och Ernest Cuneo 1988.

Vid detta laget var det bara McClory kvar i livet av dem som skapade

"Thunderball" i slutet av femtiotalet.

...och just som man trodde att affären var över för länge sen, händer

två saker ungefär samtidigt (en tveksam tillfällighet...?); den

17 november 1997 lämnar MGM Inc. in en

stämning mot Sony Pictures, där de hävdar att de köpt upp

distributionsrättigheterna till filmen '

Never Say Never Again' från Taliafilm och de vill nu ha

upprättelse för eventuella copyright-överträdelser som Sony kan ha

överskridit när de lanserat sina planer i mitten av

oktober 1997 att göra en ny serie med Bondfilmer (plus att man vill

visa för världen att Bond tillhör MGM).

Sony Pictures, å sina sida, har tagit Kevin McClorys parti och stämmer

MGM på en del av de pengar som ALLA deras Bondfilmer dragit i under

åren. Sony hävdar att McClory var en av dem bakom idén om en serie

filmer om James Bond, något som han senare aldrig fått någon ersättning

för (förutom för 'Åskbollen'

, se ovan). MGM och Danjaq anser att McClory har vilsefört Sony och att

han har inga som helst rättigheter till de övriga filmerna. Man kan ju

definitiv hålla med MGM och Danjaq i detta, men underligare saker har

hänt i domstolarna...

När Sony Pictures gick ut med meddelandet att de skulle göra en egen

Bondserie, hävdade även McClory att han, i och med

"Thunderball"-rättegången, även äger rätten till alla Bond-uppslag som

innehåller vissa inslag såsom: gömda bärplansbåtar, användandet av

Bahamas, atomvapenstölder och den sicilianska maffian. Intressant

tankegång, eller hur...? :-)

Den 29 juli 1998 förbjöd domstolen Sony Pictures

att använda sig av James Bond i något sammanhang (reklam, inspelningar

med mera) använda sig av namnet James Bond innan domstolen gör sitt

slutgiltiga beslut.

I slutet av mars 1999, en vecka innan den

slutgiltiga rättegången, gav Sony Pictures upp. I uppgörelsen

fick Sony betala MGM 5 miljoner dollar och bekräfta att de

inte hade någon rätt till att göra Bondfilmer. Det inkluderar även en ny

version av 'Never

Say Never Again'.

Men uppgörelsen gjorde också att MGM fick betala Sony 10

miljoner dollar för de globala rättigheterna till alla filmer och

rättigheterna till

filmen och

boken

"Casino Royale". De hade redan 50 procent av rättigheterna då

United Artist köpt dessa strax efter att Charles K. Feldman

(som hade rättigheterna innan) avlidit. De andra 50 procenten stannade

kvar i Colombia Pictures (som gjorde filmen). UA gick

senare ihop med MGM och Colombia köptes upp av Sony

Pictures.

MGM äger nu rättigheterna till alla Bondfilmer inklusive 'Never

Say Never Again' plus att de har rätten att filma boken "Casino

Royale".

Trots denna uppgörelse gav inte Kevin McClory upp. Han ansåg att Sony

gjort denna överenskommelse bakom ryggen på honom och skrev inte under

den överenskommelse som Sony gjorde med MGM och under

hösten 1999 började en ny rättegång mellan McClory och MGM. Denna

kamp tog slut ett halvår senare då domstolen kom fram till att han

INTE hade några rättigheter till procent i Bondfilmerna. Ett av de

stora skälen som domaren hade var att McClory hade väntat för länge

innan han gick till rätten.

I början av juni 1999 gick McClory dessutom ut

med att han fått två företag (ett tyskt och ett australiensiskt)

intresserade att börja med att göra ännu en film baserad på boken "Åskbollen",

denna gång skall den heta 'Warhead 2001'. Detta skulle sedan leda

till ytterligare Bondfilmer. Detta rann dock också ut i sanden.

Kevin McClory avled den 20 november 2006 på

Irland med stora skulder. Därmed borde alla kamper om rättigheterna av

Åskbollen vara över.

Det kan vara en intressant tanke att leka med vad som skulle hänt om

McClory slutat med sin besatthet över Bond. Filmen Åskbollen gav honom

mycket, mycket pengar. Om han istället för att kämpa emot jättarna lagt

de pengarna på att grunda ett eget produktionsbolag och gjort egna

filmer istället, det som han faktiskt hade en stor passion att göra, hur

mycket mer lycka hade han (och alla andra i denna affär) haft då?

|

Dive Site: James Bond wrecks, Nassau, Bahamas

Dive Site: James Bond wrecks, Nassau, Bahamas